WebRTC

27 Dec 2020In a continuation of earlier work on digital humans, I have been building a platform for streaming cloud-rendered avatars to browsers and apps. In this platform, content is rendered in Unreal Engine which in mid-2019 gained a pixel streaming plug-in that utilizes WebRTC to handle streaming of game content to clients over the internet. This has provided me with the opportunity to work intensely with WebRTC, and I’d like to share some thoughts about this technology.

What is WebRTC?

WebRTC is short for Web Real-Time Communications. It provides real-time peer-to-peer streaming of audio, video, and data using a relatively simple API. One of its main intents is to enable video calls between remote users in true peer-to-peer fashion using only their browsers and without requiring them to install a browser plug-in or struggle with firewall settings. WebRTC is a free, open-source standard and is supported by the likes of Apple, Google, and Microsoft (to name a few). It is still working its way through the standardization process of the IETF, but it is already supported in all major browsers and mobile platforms. Furthermore, it is already in wide use in a number of video conferencing solutions, notably Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, GoToMeeting, and others. WebRTC is certainly here to stay.

When establishing a streaming connection between two parties, the ultimate goal is for the parties to stream audio, video, and data directly to one another without going through an intermediary. This serves the dual purposes of

- reducing the total network bandwidth and compute resources consumed

- reducing the latency of the connection for a better “live” experience

However, establishing a peer-to-peer connection over the internet is a non-trivial matter.

Firewalls

Normally one or both peers are behind firewalls designed to protect them from receiving messages directly from other devices on the internet. The only messages that are allowed in through the firewall are responses to the requests that the peer itself has made. The most well-known example of this is the content received by a browser in response to requests made to a web server. The messages that are allowed through the firewall to the browser all arrive in response to the browser sending a message to the web server saying “please send me this content”. Imagine if any website could freely send data to your browser without being asked. You would probably be staring at thousands of browser tabs filled with nothing but ads!

The reason that websites are able to receive your requests for content is that they have been deliberately configured to receive such requests from the internet at large specifically for this purpose.

One key feature of WebRTC is that it hides the intricacies of establishing peer-to-peer connectivity from the application developer, so they don’t have to solve this part of the equation themselves. To do this, WebRTC relies on a number of existing standard protocols to do the heavy lifting.

Signaling

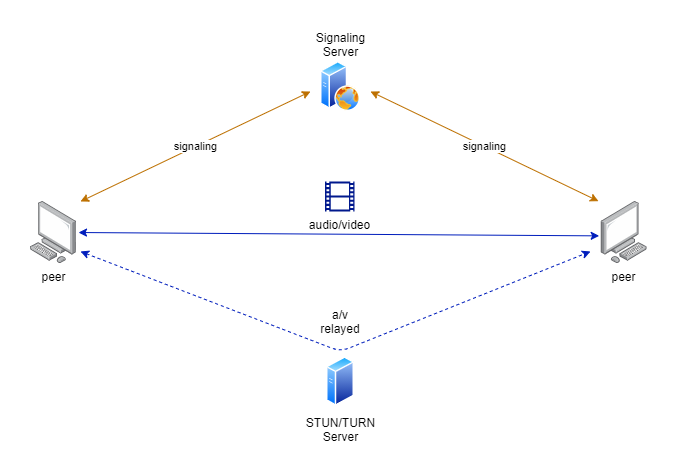

WebRTC uses Interactive Connectivity Establishment (ICE) to establish a peer-to-peer connection. Peers use a Session Traversal Utilities for NAT (STUN) server to discover their own public IP address, that is their address as seen from outside their firewall. This address is then shared with the other peer via an ICE message. Using this shared information peers are usually able to establish a direct connection across their firewalls by using “hole-punching” - which is not as sinister as it sounds - to tell their firewalls that they are temporarily willing to receive messages directly from the other peer.

In some cases, however, one or both of the parties’ firewall configurations make it impossible to establish a direct connection, and they must fall back to using a Traversal Using Relays around NAT (TURN) server to relay the streaming data between them. This is less efficient than using a direct connection, because data must pass through the TURN server before reaching its recipient. Also, someone must maintain this server and pay for the bandwidth it uses. Often a single server supports both STUN and TURN functionality.

“Wait a minute”, you may be thinking, “if the peers cannot initially exchange messages directly, then how do they exchange ICE messages?” ICE messages are usually exchanged via an intermediary such as a website or other service to which both parties connect for this exact purpose. In this context the intermediary is referred to as a signaling server, and the exchange of ICE messages as signaling. The WebRTC standard does not prescribe how signaling is accomplished, which is deliberate in order to provide as much flexibility as possible. In principle, signaling messages could even be transmitted by carrier pigeons or smoke signals.

Another important standard used as part of WebRTC signaling is the Session Description Protocol (SDP). SDP messages describe the types of media (e.g. video, audio, and data) that each peer wants to send and receive and which media encodings and formats they are capable of using. Each peer also generates and includes cryptographic keys for one-time use in order to enable end-to-end encryption of streaming data.

Once SDP and ICE have done their job the peers now have a path to start streaming data to one another. At this point yet another standard, the Real Time Streaming Protocol (RTSP), is used to actually send and receive multimedia data over the established connection. I won’t get into the many details of RTSP as that could easily fill a separate post, but suffice it to say that this takes care of things like optimizing data streams for the available bandwidth, retransmission of lost data, and many other essentials of successful streaming.

Simple API

At this point you probably have the impression that WebRTC is quite a complex beast supported by many additional standards and protocols and that using WebRTC in your own development projects might be rather daunting. Certainly building something comparable from scratch would be a monumental undertaking. But how difficult is it for a developer to work with WebRTC?

The JavaScript API that WebRTC exposes to web developers in the browser is deceptively simple. It has just three main entry points:

navigator.mediaDevices.getUserMedia()– gathers information about available devices (microphones, camera, and the screen) and their capabilities while prompting the user for permission to access these devicesRTCPeerConnection– manages the connection to the remote peer, including the actual audio and video streamsRTCDataChannel– manages data channels to exchange custom messages (not audio and video) with the peer via the RTCPeerConnection

The bulk of the interaction with a custom web application will be with RTCPeerConnection. It has a multitude of methods and callbacks that must be orchestrated with both the frontend code and the signaling server. However, it does all the heavy lifting associated with ICE, SDP, and RTSP, allowing the developer to concentrate on their application-specific functionality while getting streaming audio and video almost for free. The RTCPeerConnection API produces and consumes all the signaling messages for you – all you have to do is manage the transmission of these messages between peers.

I won’t clutter this post by including code, since code samples are plentiful. Examples can be found of functioning websites offering simple WebRTC calls between connected clients. Some are as short as a few hundred lines of JavaScript. WebRTC APIs are also available for app developers on Android and iOS, and these APIs closely resemble the browser API. This makes it about as easy to incorporate WebRTC in a mobile app as in a web page.

This out of the box simplicity is great when you are developing apps or websites for streaming between users on different frontend devices. But what if you are working with a client/server scenario?

WebRTC and digital humans

Initially, the digital human scenario may look more like a client/server scenario than a peer-to-peer scenario. After all, rather than connecting to another user who is physically located somewhere else in the world, a user connects to a website or service on the internet in order to interact with an avatar. However, this is easily viewed as a special case of peer-to-peer by considering the avatar not as a service but as a peer on an equal footing with the human user.

While the sample web server and scripts provided by Unreal with their pixel streaming plug-in are straightforward to get up and running, and they do a good job for demonstration purposes, they are not directly suited to the digital human scenario. The sample scripts seem to be designed mainly to allow multiple spectators to view a game being played by a single player, while the digital human scenario calls more for a one-to-one interaction between a human and an avatar. Additionally, the scripts do not address issues of scaling to 10s, 100s, or even 1000s of such simultaneous interactions.

More importantly, the digital human must be able to see and hear the user, and the pixel streaming plug-in does not support the streaming of audio and video from the user to Unreal. The solution that I am involved in building side-steps this limitation by using a separate server-side component to receive the audio and video from the user and perform Voice Activity Detection (VAD) and subsequently speech recognition and emotion detection. Basically, two separate WebRTC connections are established, one between Unreal and the user and the second between the user and the VAD component. On the server side, the VAD component is able to communicate directly with Unreal, because they don’t have to contend with the limitations otherwise imposed by firewalls.

Implementing the server side VAD component introduced an additional challenge. The WebRTC APIs described above are designed to run within their respective client frameworks either as part of a mobile app or within a browser. They are therefore not applicable in a server setting. Luckily there are libraries available written in a variety of server side programming languages such as node-webrtc for NodeJS and aiortc for Python.

The most feature complete and high-performance library I have found is GStreamer. GStreamer is a multiplatform multimedia framework written in C, and includes a feature-rich WebRTC plug-in even though its functionality goes far beyond WebRTC. It also has solid language bindings for most popular programming languages, which means that it can be used in a variety of settings including servers and embedded devices.

Summary

Even though WebRTC is not yet a finalized standard, I think it is a no-brainer if you want to integrate peer-to-peer audio/video streaming in your own web application or mobile app. As I have shown, it is also useful in other contexts where its peer-to-peer nature is perhaps not so readily apparent. WebRTC is a great example of how a ton of functionality and complexity can be hidden behind a small, deceptively simple API. As is often the case, the devil is in the details, and moving beyond basic examples quickly forces you to consider those details.